“Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence” (by Ted Lewis)

Advent Carol Essay by Ted Lewis, Christmas Season 2022/2023

| Ἀλληλούϊα, Ἀλληλούϊα, Ἀλληλούϊα |

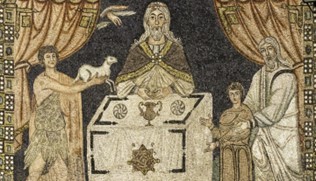

“Let All Mortal Flesh,” with its haunting minor mood, may be one of the oldest songs associated with Christmas, though in its original context it was part of a eucharistic liturgy. St. James the Lesser, first Bishop of Jerusalem, is thought to have written the core text in Syriac in the 5th century. It was spoken or sung during the Liturgy of St. James as the bread and wine were brought forward. This English text, written in the Victorian era, is based off a Greek version from the Byzantine era:

Let all mortal flesh keep silent, and stand with fear and trembling, and in itself consider nothing earthly; for the King of kings and Lord of lords cometh forth to be sacrificed, and given as food to the believers; and there go before Him the choirs of Angels, with every Dominion and Power, the many-eyed Cherubim and the six-winged Seraphim, covering their faces, and crying out the hymn: Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia.

You might ask, “How did this text work its way into a Christmas hymn? It has no reference to incarnation or birth.” Let’s first consider the biblical sources for this song, and then learn about its genesis in the Victorian period.

The main imagery draws people into the temple zones of Isaiah 6 and Revelation 4 & 5 where God’s glory is revered. Human worshippers are not alone; at center stage are angelic hosts who honor the “King of Kings and Lord of Lords.” This regal phrase comes from Revelation 19:16 and 17:14, with clear reference to the Lamb who overcomes. Winged Cherubim and Seraphim remind us that God is all-seeing and all-consuming, hence, a God actively involved in our sanctification.

The phrase “let all mortal flesh be silent” likely comes from Habakkuk 2:20, but Zechariah 2:13 is also a source: “Be silent, all flesh, before the LORD” (KJV). Silence may be the proper response for anyone encountering the “positive infinity of the living yet superpersonal God” (C. S. Lewis). Habakkuk also roots the response in the context of controlling forces. Babylonian violence is not sustainable; idols likewise are a dangerous pseudo-force. In stark juxtaposition is God’s authentic power which invites our silence with “with fear and trembling.” How fascinating that a later Zechariah, in Luke 1, is literally silenced by an angel!

Themes of worship and sanctification naturally lead into incarnation. The central line is eucharistic: “cometh forth to be sacrificed, and given as food to the believers.” The sacrificial King comes forth. There’s a proper Advent phrase. All powers are conquered by the Lamb who came forth by relinquishing power. This is “food” to all who reorient their lives according to the paradoxical pattern of surrender and resurrection. It is our strength in the midst of our vulnerability.

Little wonder, then, that after this ancient text was translated into English in 1864 during the Oxford Movement, it was adapted into a hymn by Gerard Moultrie, an Anglican priest. The full text is listed below, but I’d like to highlight his inclusions that amplified the incarnational theme:

- Christ our God to earth descendeth

- King of kings, yet born of Mary

- Lord of lords, in human vesture

- In the body and the blood

- Light of light descendeth

These additions related the song to Christmas, which, of course, means “Christ’s Mass”. There is no physical eucharist without a physical resurrection; there is no physical resurrection without a physical death; there is no physical death without a physical birth. Attention to the physical shows how the spiritual animates every aspect of the Christ-mission, no less than Christ’s Immanuel Presence.

But what of the tune with the haunting melody? The tune PICARDY comes from a book of French medieval folksongs, Chansons Populaires des Provinces de France, published in 1860. Composer Ralph Vaughan Williams later paired it with Moultrie’s verses in 1906. In contrast to the triumphal, major-chorded hymn, “Holy, Holy, Holy,” this minor-tuned song deepens our reverence as quieted mortals.

When we think about the song’s development, we are struck by its many layers: its primal roots in ancient temple visions of angelic worship, its Eucharistic usage in the Patristic era, its continued use in Eastern Orthodox liturgies, its incorporation into verse during the Oxford Movement, and its marriage to a contemplative French folk tune. What a weave of contributions!

We live in unprecedented times where an increase of social pressures, pandemic challenges, environmental changes, political polarizations, and relational divisions push people into isolating zones of ‘survival mode.’ The resulting anxiety and depression is manifested around us on a daily basis. “This calls for patient endurance and faithfulness on the part of the saints,” (Revelation 13:10; 14:12). Social upheavals are not unique to modern times. Isaiah faced Assyria’s imperial forces; John encountered Roman totalitarianism. The “powers of hell” still find institutional outlets. And yet it is in such times that grand visions of worship are so important, even subversive. They provide the ultimate survival tactic. They ground the faithful in Something larger than themselves. The silencing that results from such visions is not only in response to what is seen; it is also for a way of being in the midst of troubled times. “In quietness and trust is your strength” (Isaiah 30:15).

This centered way of being amidst all the noise and chaos makes a strong case for a worship community. In our limited mortal flesh we need each other to remember good traditions; we need each other to sustain our bearings and our best commitments. Relational communion has to be part of our eucharistic communion. In brief, we need to be in good company (literally, together with bread) if we are going to make it through troubled times. As we are drawn into the awe and mystery of seraphic and cherubic worship, we sing aloud a trio of Alleluias, even in a minor key, to strengthen our hearts. Even a “broken hallelujah,” as sung by Leonard Cohen, gets God’s best attention!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1RqqcUTBhHY&t=6s

- Let all mortal flesh keep silence,

And with fear and trembling stand;

Ponder nothing earthly-minded,

For with blessing in His hand,

Christ our God to earth descendeth,

Our full homage to demand. - King of kings, yet born of Mary,

As of old on earth He stood,

Lord of lords, in human vesture,

In the body and the blood;

He will give to all the faithful

His own self for heav’nly food.

- Rank on rank the host of heaven

Spreads its vanguard on the way,

As the Light of light descendeth

From the realms of endless day,

That the pow’rs of hell may vanish

As the darkness clears away. - At His feet the six-winged seraph,

Cherubim with sleepless eye,

Veil their faces to the presence,

As with ceaseless voice they cry:

“Alleluia, Alleluia,

Alleluia, Lord Most High.”

Ted Lewis is a Restorative Justice Consultant and Trainer for the Center for Restorative Justice & Peacemaking at the University of Minnesota, Duluth. Since the mid-90s he has been a practitioner and trainer in the fields of conflict resolution and restorative justice. Ted has provided workshops and facilitation services for church communities, and recently founded the Restorative Church project. He now lives in Duluth.

Thank you, Ted, for this deep look into that long-ago world yet also our world. Alleluia.

Very fine reflection on one of my all-time favorite hymns. Thank you, Ted.

Cindy Peterson-Wlosinski

Very inspiring! I’ll be humming that hymn in my head all day.